Why California Must Oppose SB 1410: A Primer on the Importance of SB 743 (2013)

The California Senate Committee on Environmental Quality will hear a bill on April 25th, SB 1410, which would pose a dangerous step backward for California’s ability to meet its climate and equity goals.

SB 1410 would mandate the revision of the Vehicle Miles Traveled (VMT) based methodology to analyze transportation impacts under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) that was carefully developed over many years with cross-interest input, pursuant to SB 743 (2013). The proposal would restrict this new methodology to solely consider GHG emissions, rather than additional land use and multi-modal transportation factors as directed by SB 743. SB 1410 would further limit the application of the new methodology only to Transit Priority Areas (TPAs), thereby eliminating the requirement for any transportation-specific impact analysis under CEQA for all other areas.

CEQA’s current VMT-based impact analysis is perhaps the strongest policy lever we have to encourage (and reduce the costs of) location-efficient housing and infrastructure to help meet our greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction mandates, conserve natural and working lands, and improve public health outcomes and equitable access to opportunity for all Californians. We strongly recommend that the Committee decline this proposal to eliminate this project analysis requirement, as we find it to be extremely problematic in multiple ways, explained in more detail below.

If your organization wishes to sign-on to PCL’s opposition letter,

Please do so here

OR contact PCL Policy Director, Matt Baker, matthew@pcl.org

SB 743 was passed in 2013 to correct problems that the traditional transportation impact analysis under CEQA, “Level of Service” (LOS), posed to meeting state climate mandates and meeting our multi-modal transportation needs, particularly for infill development. With LOS being a metric that only considers automobile capacity, a project’s transportation impacts could only be mitigated by adding more automobile capacity without regard for other mobility options in context to surrounding land uses. The VMT-based methodology finally enacted in 2020 pursuant to SB743 corrected this problem by offering a metric that allows for consideration of existing and potential multi-modal transportation options, in relation to the project’s surrounding land-uses, allowing for greater density and closer proximity of housing, jobs and essential services.

SB 1410’s proposal to revise this methodology to only consider GHG emissions would focus the weight of transportation impact analysis and mitigation on vehicle technology alone without regard for consideration of other mobility options and the project’s relation to surrounding land uses that could reduce the need to drive in the first place.

The proposal would require a redundant analysis of GHG emissions, which is already a requirement under CEQA, and by only requiring this additional analysis in TPA’s, would disincentivize development in transit-oriented areas where we need it most.

The bill’s original language would have reverted all transportation impact analysis outside of TPAs to the LOS methodology. This approach would inhibit infill development in all other urbanized areas, which we greatly need to accommodate further growth of transit and active transportation networks outside of current TPAs. The current proposal would eliminate a transportation-specific analysis requirement under CEQA all together for all areas outside of TPAs, except for “…impacts related to air quality, noise, safety, or any other impact associated with transportation,” existing code from SB 743. Consideration of transportation factors associated with these other impacts analyzed under CEQA does not offer a metric for analyzing transportation needs of a project in relation to surrounding facilities and uses specifically. Specific evaluation of transportation impact and need is a fundamental function of CEQA, and VMT is the correct metric for this analysis.

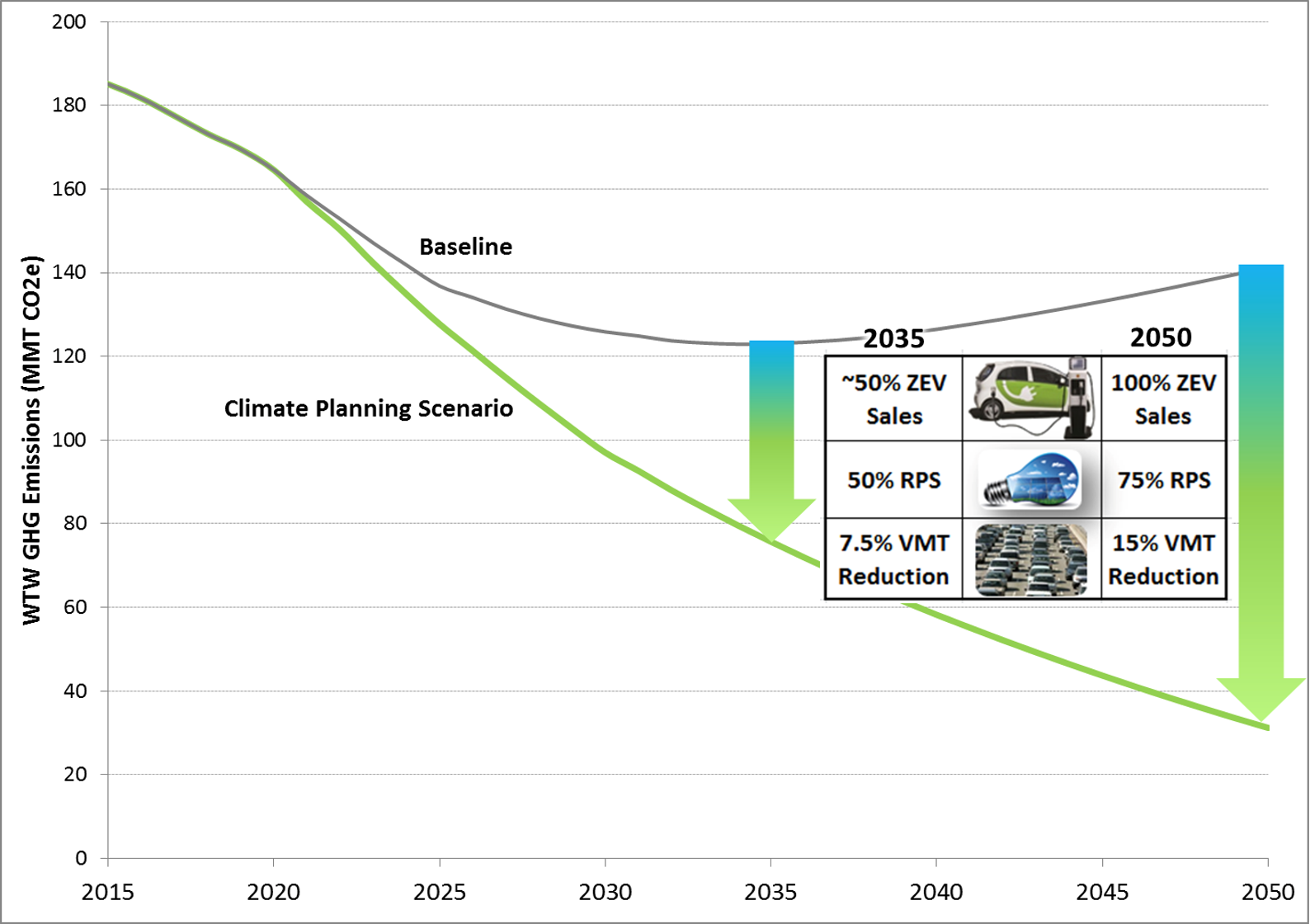

GHG reduction is an extremely important biproduct of VMT reduction, but GHG and VMT are not the same. As written in these pages many times before, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) has found that significant reduction of VMT is needed to achieve GHG reduction targets mandated by AB32 and SB32, beyond what is currently projected in our regional transportation plans.

“…Through developing the Scoping Plan, CARB staff is more convinced than ever that, in addition to achieving GHG reductions from cleaner fuels and vehicles, California must also reduce VMT. …there is a gap between what SB 375 can provide and what is needed to meet the State’s 2030 and 2050 goals. In its evaluation of the role of the transportation system in meeting the statewide emissions targets, CARB determined that VMT reductions of 7 percent below projected VMT levels in 2030….In 2050, reductions of 15 percent below projected VMT levels are needed. …It is recommended that local governments consider policies to reduce VMT to help achieve these reductions, including: land use and community design that reduces VMT; transit oriented development; street design policies that prioritize transit, biking, and walking; and increasing low carbon mobility choices, including improved access to viable and affordable public transportation and active transportation opportunities. It is important that VMT reducing strategies are implemented early because more time is necessary to achieve the full climate, health, social, equity, and economic benefits from these strategies…”

(CARB, 2018 AB 32 Scoping Plan Update, pg. 101).

It is necessary to consider the relationship between our transportation and land use projects as a function of VMT as an explicit impact under CEQA, separate from other GHG reduction factors.

Arguments by proponents of the bill that assert that VMT regulation is adding to the costs of housing are incomplete and misleading. Like all impact mitigation, VMT mitigation only adds costs to a project where there is an impact. VMT impacts relative to the existing per capita VMT of the locale must be mitigated, for example, where housing is being built that is not in proximity to jobs, services and alternative mobility options. It was precisely the purpose of SB 743 to add cost to inefficient development, to incentivize development that is more efficient, ultimately lowering the cost of efficient housing and infrastructure.

Cumulatively, the cost of development, including housing, in ever-growing efficient areas will go down because:

- Development in low VMT areas is largely exempt from conducting the new transportation impact analysis, lowering environmental review costs

- Mitigation from VMT increasing projects will be used to reduce costs of low-VMT infrastructure and housing

- Cost of living will be reduced (and quality of life increased) by reduced transportation costs, and improved health outcomes associated with less air pollution and increased options for active transportation.

Further, the long-term overall economic benefit to the state and its people in improved climate resilience and air quality, perseveration of natural and working lands, improved health outcomes and more equitable access to opportunity—all co-benefits of VMT reduction—will ultimately dwarf any near-term added impact fees on housing being planned in inefficient areas.

SB 743 was one of the most transformative laws passed in the nation in the last decade. As with all transformative public policy, there will be growing pains. The new transportation impact analysis has only been enacted for less than two years, and there are indeed implementation challenges, but these challenges can, and are, being worked out administratively.

The still-nascent 743 methodology, if implemented effectively, stands to be one of the strongest policy tools we have to meet California’s climate and equity goals, and must be allowed to take its course.